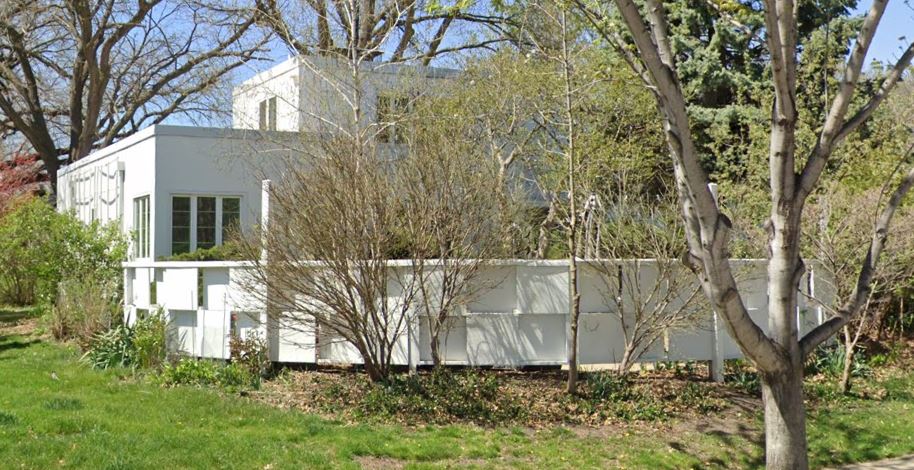

One of the most common architecture designs of the 1930s was Streamline Moderne. Art Deco’s less flashier cousin, it features designs and materials like stucco, chrome, straight-lines, rounded corners, and glass.

4028 Ovid Avenue (1939):

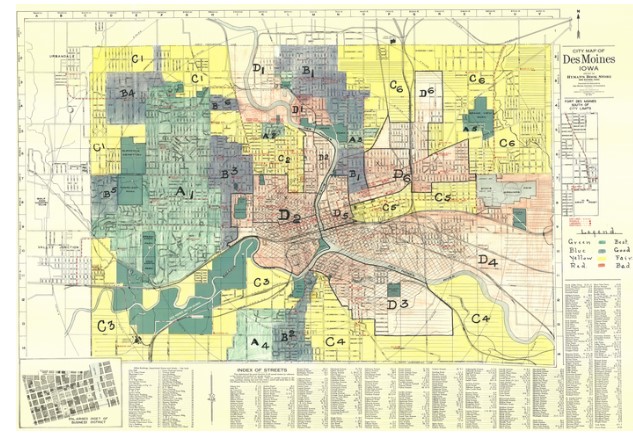

The land in Ashby Woods was originally owned by Newton B. Ashby and B.C. Hopkins. In the 1920s, developers parceled off the land, advertising the area as having many trees and being close to Beaverdale and local schools. The neighborhood was subject to restrictive covenants: only a white person could purchase a lot and build a house with as little as $50 down and 1% interest.1

3940 Beaver Avenue (1939):

The Hoyt Sherman Trust Estate began parceling off land in Kimble Acres in 1912. Located at Beaver and Douglas Avenues, real estate agents advertised easy access to the area via main roads (Beaver and Douglas) and close proximity to the Urbandale streetcar. Buyers could purchase a tract with no interest, no taxes, just $10 down and a small monthly payment. The advertisements did not specify whether the area had restrictive covenants.2

1900 44th Street (1939):

The property was originally owned by the Hickman family. The original 160 acres were parceled and sold, with Hickman Acres being one such section platted in 1922. Developers advertised the area as “Acreage for Modern Homes.” The land was well-drained and had sewer, electricity, and easy access via the paved Hickman Avenue. It was also close to Perkins Elementary School, a high school, colleges, and churches. Buyers could purchase a lot for $10 down, $10 a month, with 6% interest. Guy B. Brunk was the realtor. The advertisements did not indicate whether the area had restrictive covenants.3

4816 Grand Avenue (1937):

This tract of land was developed by L.P. Brown of Des Moines in 1923. It was bordered by Grand Avenue to the north and Greenwood Park to the east. Advertisements labeled the division “Westwood.” Selling points included Greenwood Park, close proximity to Roosevelt High School, and access to the Ingersoll streetcar loop. The area was subject to restrictive covenants.4

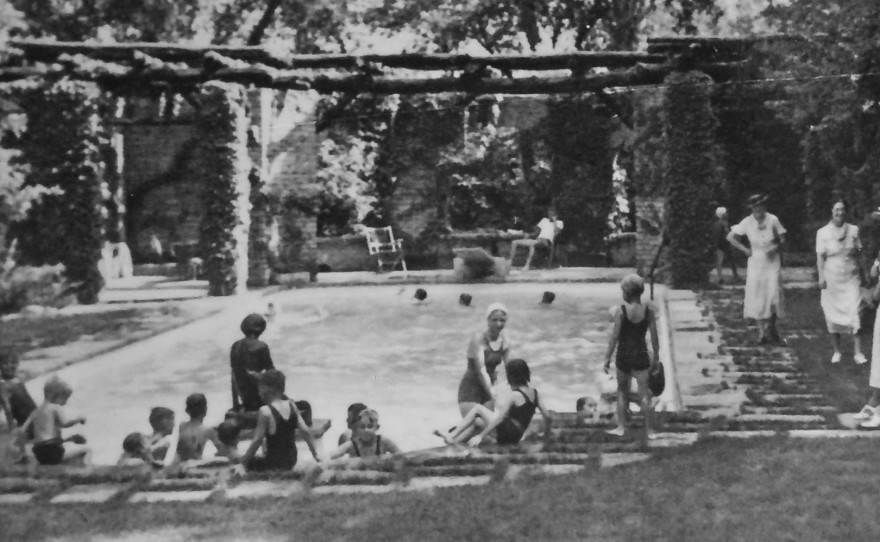

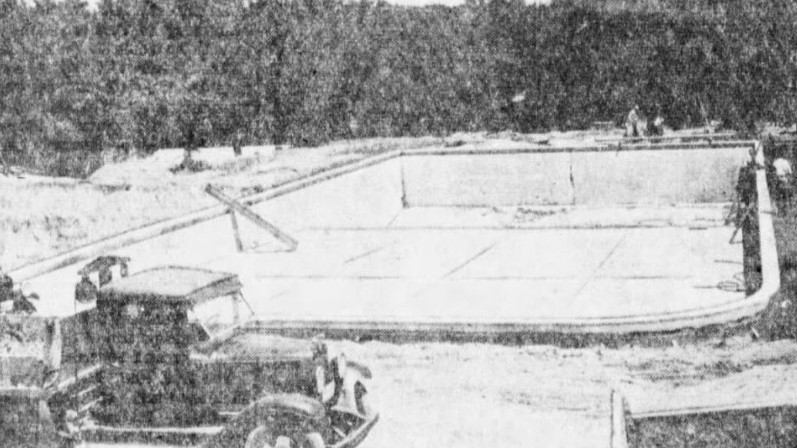

2027 Nash Drive (1938):

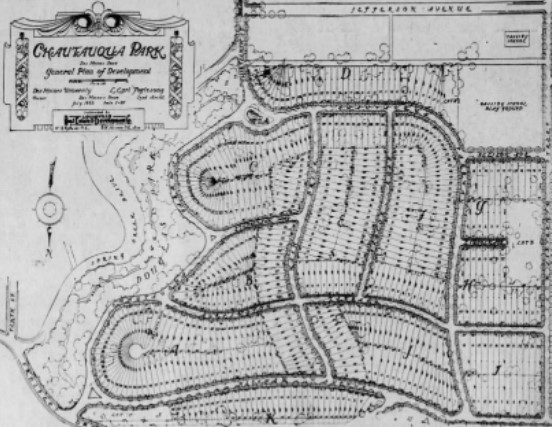

The property was originally used to house visitors and entertainers during the early days of the Chautauqua circuit. Des Moines College purchased the land for development prior to World War I, then sold it to a St. Louis developer in 1923. The area was subject to restrictive covenants.5

2633 Fleur Drive (1934):

H.S.M. said of this house in 1935, “A 19-gun salute to Earl Butler and the modernistic house he’s building—that’s the sort of pioneering we need right now.” Earl Butler wanted a home that would withstand the Iowa elements and be economically sound. Some of the amenities this house provided were heating, air conditioning, a freezer, a refrigerator, and an ‘electric eye’ for opening each of the three-stall garages. The house also had a ramp connecting all three floors to limit accidents on stairs. Today, the Butler mansion is home to the Italian American Cultural Center of Iowa.6

900 Mulberry Street (1937):

The old Lincoln Grade School was demolished in favor of a “modern structure” in the 1920s. Until the fire department headquarters was built, the property served as a parking lot, generating revenue for the city. The headquarters, designed by Proudfoot & Rawson, was part of the New Deal’s Public Administration project.7

Additional Sources:

- “Iowa’s Concrete Houses of the 1930s.” Architectural Observer. 16 May 2020. Accessed: 30 August 2025.

- “Des Moines Breaks Ground on Italian-American Culture Center.” KCCI. 10 July 2025. Accessed: 30 August 2025.

Sources:

- “4028 Ovid Avenue.” Polk County Assessor. Des Moines, Iowa. 2005. Accessed: 30 August 2025. “Going Fast!” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 27 May 1927, 35. “Lots for Sale.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 15 July 1934, 50. “Rain Delay Opening.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 13 May 1927, 5. ↩︎

- “3940 Beaver Avenue.” Polk County Assessor. Des Moines, Iowa. 2025. Accessed: 24 May 2025. ”City’s Business, The.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 2 April 1924, 5. “Kimble Acres.” Official Plat of the South 1/2 of the S.E. 1/4 of Section 19 T. 79. R24. 27 June 1912. Polk County Accessor. Accessed: 30 August 2025. ”Kimble Acres.” The Register and Leader. Des Moines, Iowa: 11 May 1913, 6. ”Real Estate Transfers.” The Register and Leader. Des Moines, Iowa: 19 February 1913, 9. ↩︎

- “1900 44th Street.” Polk County Assessor. Des Moines, Iowa. 2005. Accessed: 30 August 2025. ”Don’t Fail to see Hickman Highlands.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 05 May 1922, 25. “Hickman Highlands an Official Plat of the N.E. 1/4 o f the N.E. 1/4, of Section 31, Twp. 79N., R. 24W of the 5th P.M. Iowa.” 25 April 1922. Polk County Accessor. 2025. Accessed: 30 August 2025. McLaughlin, Lillian. ”Charming Old Home on ‘Hickman Farm’.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 01 July 1967, 18. ”See Hickman Highlands.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 25 April 1922, 17. ↩︎

- “4816 Grand Avenue.” Polk County Assessor. Des Moines, Iowa. 2025. Accessed: 24 May 2025. “L.P. Brown Dead at 78.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 18 June 1958, 16. ”L.P. Brown’s Official Plat of Lot 1 Westwood, Section 12, 78-75.” 22 March 1923. Polk County Accessor. Accessed: 30 August 2025. ”West End.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 03 June 1923, 36. ”Westwood.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 25 November 1923, 44. ”Westwood.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 19 April 1924, 11. ”Westwood.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 15 June 1924, 51. ↩︎

- “2027 Nash Drive.” Polk County Assessor. Des Moines, Iowa. 2025. Accessed: 24 May 2025. Elm, L.M. “Land Deed Restrictions (1930s).” L.M. Elm, Historical Novelist. 24 April 2022. Accessed: 30 August 2025. ↩︎

- H. S. M. “Over the Coffee.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 25 June 1935, 16. “House for Earl Butler, Des Moines, Iowa.” Architectural Forum 67, no. 3 (1937): 179–86. Bolten, Kathy A. ”Italian American Cultural center of Iowa Purchasing Iconic Butler Mansion for $3.3 Million.” Business Record. 20 December 2020. Accessed: 20 April 2020. ↩︎

- “City Clears Way for New Fire Station.” Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa: 06 January 1937, 13. ”Des Moines Social Club Headquarters.” Iowa Architectural Foundation. Des Moines, Iowa. 2025. Accessed: 30 August 2025. ”Farewell to Old School.” Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa: 25 April 1924, 12. ↩︎