Dorothy Schwieder, a renowned historian, summed up late 1930s Iowa scholarship in one brief paragraph (while entire chapters of this book were devoted to 1929-1932 in extensive, exhaustive detail, but I digress…):

By 1937 economic conditions had improved for both rural and urban dwellers in Iowa. The Agricultural Adjustment Act, passed in 1933, had brought improved conditions for Iowa’s farm families. In 1932 national farm income had totaled $5.5 billion, and that amount had risen to nearly $8.7 billion in 1935. Though participation in the A.A.A. was voluntary, approximately 75% of Iowa farmers took part. Many Iowans talked in terms of the Depression coming to an end in 1938.1

Dorothy Schwieder. Iowa the Middle Land. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1996, p. 272.

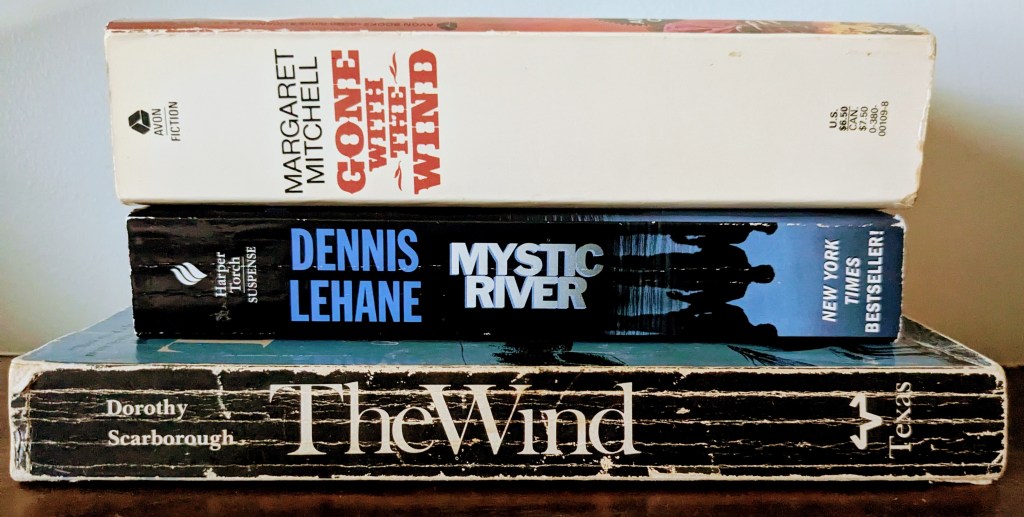

If this is the extent of late 1930s Iowa scholarship, where does a writer of historical fiction go in search of sources?

WPA Guides:

History:

48 state guides were published. Each guide provided general state history and offered suggested tours through varying parts of the state.2

Iowa:

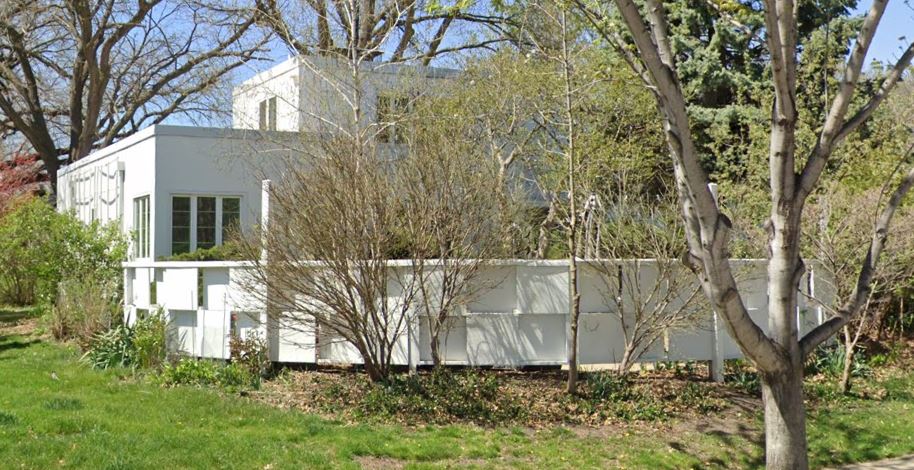

Originally published in 1938 as Iowa: A Guide to the Hawkeye State, this tome covers Iowa in detail. General history, cities, maps, and suggestive travel guides. There are places in Des Moines that were either glossed over or intentionally excluded (see Maps: redlining).3

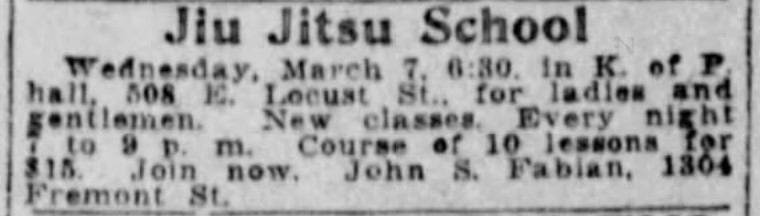

Newspapers:

Des Moines Register:

Gardner Cowles, Sr purchased the Register and Leader in 1903. By 1915 newspaper’s name changed to The Des Moines Register. Cowles, Sr. pushed distribution via train and truck (Or any transportation necessary to get his newspapers into readers’ hands). This newspaper focused on world and state-wide issues. It was Des Moines’ morning newspaper.4

Des Moines Tribune:

This was Des Moines’ evening newspaper. While it was also owned by the Cowles family, the newspaper maintained its own staff and was often considered a rival of the Des Moines Register. This paper covered Des Moines and the surrounding towns exclusively.5 (5).

Bystander:

Was the state-wide Black newspaper. Originally published as the Iowa State Bystander in 1894. By 1937 the newspaper was known as The Bystander. It was owned by James B. Morris a lawyer and political leader.6

Maps:

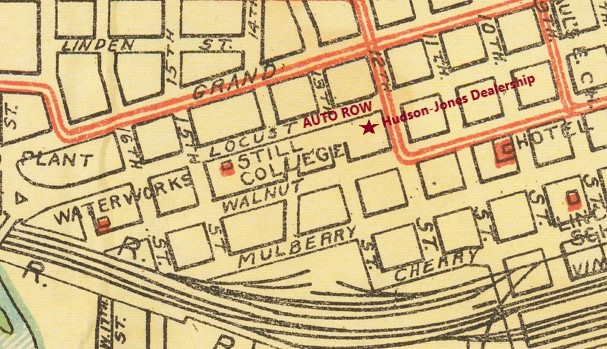

Regular Map:

One of my favorite maps to reference is The Official Map and Guide of Des Moines. Des Moines, Iowa: Midland Map & Engineering, Co., 1920. It has wonderful details of parks, official buildings, and call-out locations. While this map is a decade earlier than my story (there are lots of places I know did not exist in 1920 but did in 1937), this map is still a great resource for getting a visual clue of Des Moines, Iowa.7

Redlining:

Midland Map & Engineering’s 1920 map tells only part of the story. Where people lived and why is another. The mortgage industry and the U.S. government developed redlining maps from 1934-1938. Government agencies used and strengthened local segregation practices by establishing a color-coded system to highlight reinvestment possibilities. Areas deemed unfit for investment (predominately non-white neighborhoods), were given a red status. One such redlining map may be found here.8

One of the joys and frustrations of historical fiction is the hunt for details. It can also be an excuse to avoid writing. There are a couple of rules I follow so I don’t fall into the research trap. (1) 1:2 Rule: One primary source for two secondary sources. (2) I stop digging when secondary sources cite books I’ve already read. The setting is an important fiction element and should be a character of its own. Its job should be to shape the character(s) and establish the rules of society. Will the characters follow society’s rules? Or break them? What are the consequences of doing either one? Maybe answering those questions is why I love reading and writing historical fiction.

My own personal map of Des Moines in 1937 is found here.

Sources: